AI is no longer knocking on the doors of Philippine classrooms, it has already walked in. From basic education to universities, artificial intelligence is reshaping how students learn, how teachers teach, and how decisions are made. But amid the buzz of innovation, one critical question lingers: Where does the government truly stand, not just in policy statements, but in practice, in priorities, and in protecting equity and ethics?

A Revolution, or Just a Technocratic Band-Aid?

In February 2025, the Department of Education (DepEd) launched the Education Center for AI Research (E-CAIR). Framed as a hub for innovation, E-CAIR’s mandate spans personalized instruction, data-informed policymaking, and streamlined school administration. It’s a bold step aligned with the government’s push for a “modernized” education system.

Tools for Early Detection, or New Risks in Disguise

Take, for instance, DepEd’s Project SABAY (Screening using AI-Based Assistance for Young Children), which seeks to identify developmental delays in young learners using AI. The initiative functions through the collection of data from various sources, teacher and parent observations, results from digital assessments, and possibly even behavioral cues captured via audio or visual inputs. These data streams feed into machine learning systems trained to detect patterns that may point to developmental issues.

However, the output is not a definitive diagnosis. Instead, the AI provides probabilistic risk assessments, essentially flagging students who may need further evaluation by specialists. Automating these initial screenings could drastically reduce delays in intervention. More impressively, the system is designed to adapt over time, refining its accuracy through longitudinal data collected for each student, potentially enabling more precise support strategies.

This may sound like a leap forward, but without sufficient infrastructure or access to specialists, especially in underserved schools, the benefits may be unevenly distributed. What begins as a tool for early detection could become a source of misclassification if used without proper oversight or understanding.

Platforms, Power, and Pedagogy

This interplay of promise and concern continues with the integration of AI-powered platforms, like Microsoft’s Reading Progress and Reading Coach. These tools assess oral reading skills by transcribing speech, identifying fluency issues such as mispronunciations or omissions, and delivering immediate, personalized feedback. Teachers receive dashboards summarizing both individual and class performance, enabling more targeted literacy instruction.

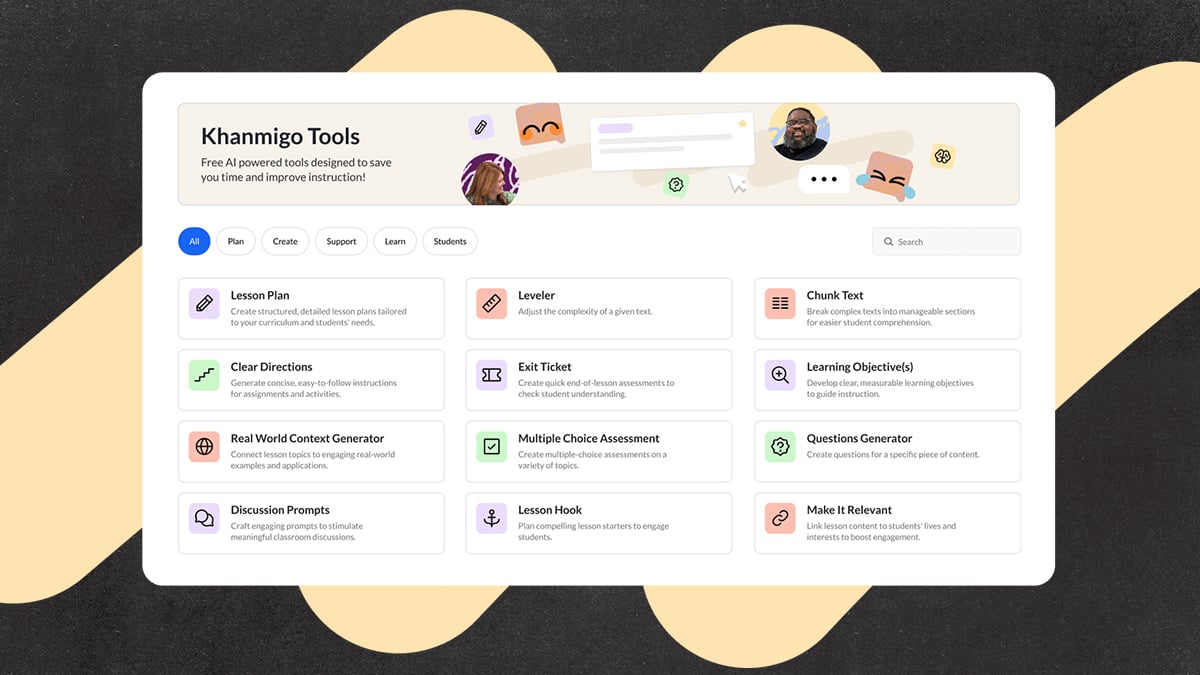

Similarly, Khan Academy’s AI assistant, Khanmigo, enhances learning by guiding students through complex concepts using natural language processing. It engages them in conversations, helps generate ideas, and prompts them toward deeper critical thinking. Beyond students, it also offers support to educators, suggesting instructional materials and monitoring learning progress.

But the widespread use of these foreign-owned platforms raises significant questions about sovereignty, data ethics, and educational philosophy. Who owns the data being generated? Who is responsible when the AI errs? And what values are embedded within these algorithmic tutors?

When these systems are plugged into schools with little local oversight, there’s a risk of normalizing pedagogical models that do not reflect Filipino contexts. In essence, we may be importing not just tools but entire ideologies about what learning should look like.

Beyond ideology, there’s also the question of cultural fit. Most of these AI platforms are designed with Western learners in mind. Often monolingual, digital-native, and guided by specific learning models. Yet in the Philippines, classrooms are multilingual, diverse in learning contexts, and rooted in localized experiences. If these AI systems aren’t trained or adapted to accommodate indigenous languages, regional dialects, or culturally relevant content, they risk reinforcing educational exclusion. In short, the tools may be “smart,” but they may not be locally intelligent.

AI tools in the hand of students

While teachers are using AI platforms for instruction, students are also exploring these tools independently, raising new challenges. However, their increasing use also raises questions about academic integrity and long-term skill development. In some cases, students may rely too heavily on AI, completing tasks without fully engaging with the material.

A thoughtful response would involve establishing clear, national guidelines on how AI should be used in education. This includes defining acceptable forms of assistance, helping educators recognize AI-generated content, and integrating AI literacy into the curriculum. Teaching students to use AI responsibly, not as a replacement for effort but as a tool for learning, can help strike the right balance.

At present, most efforts are centered on innovation and infrastructure. Discussions around ethical use and responsible practices are emerging but remain limited.

Bureaucratic Speed vs. Systemic Gaps

The promise of AI extends beyond the classroom into the administrative machinery of education. E-CAIR envisions AI helping predict enrollment trends, identify students at risk of dropping out, optimize resource distribution, and automate routine tasks such as report generation or application processing. In theory, this means teachers can spend more time teaching and less time buried in paperwork.

Yet again, the reality is layered. Many schools, especially in rural areas, lack the infrastructure to even begin implementing these systems. Without adequate investments in hardware, connectivity, and teacher training, the gulf between schools will only widen. Efficiency, in this context, becomes a privilege.

Quiet Moves in Higher Education

While much of the national spotlight is on DepEd’s basic education programs, higher education institutions are also exploring AI integration. The University of the Philippines Open University (UPOU) stands out with its proactive approach. In 2024, it issued some of Southeast Asia’s first academic guidelines on ethical and responsible AI use. Learning analytics, AI-assisted grading, and customized curriculum pathways are gradually being explored within the framework of student rights and institutional integrity.

However, beyond pioneering institutions like UPOU, most universities lack a coherent strategy for AI adoption. The Teacher Education Council’s review of the pre-service curriculum to incorporate AI literacy is a move in the right direction, but systemic change remains elusive. The momentum is there but without national coordination, progress risks becoming isolated and uneven.

Learning from the World: What Other Countries Are Doing

Internationally, many governments have taken a proactive approach to managing the intersection of AI and education—an approach the Philippines can draw lessons from.

Developing AI literacy has been a key strategy. Countries like South Korea aim to incorporate AI into curricula at all levels by 2025, while Singapore is investing in training programs for teachers to build confidence and understanding of AI tools. Japan takes a different route by encouraging the use of AI errors as learning opportunities, nurturing critical thinking rather than blind acceptance of algorithmic outputs.

At a more strategic level, nations like China, the UK, and India have incorporated AI in education within their broader national AI strategies. Governments have backed this up with public funding for AI research and infrastructure. Australia and New Zealand, meanwhile, offer national guidelines while empowering schools with implementation autonomy.

Adopting these models in the Philippines would require tailored adaptation. Local infrastructure disparities must be addressed to avoid deepening the digital divide. National AI literacy initiatives must also consider multilingualism, cultural nuances, and the limitations in teacher training systems. Still, many principles like ethical clarity, inclusive policymaking, and investment in teacher training can guide local policymakers toward a more coherent and equitable AI agenda.

Unwritten Rules and the Path Forward

With the growing number of AI-powered initiatives in education, the Philippine government needs a comprehensive, enforceable framework to guide implementation. For instance, pilot programs make headlines, but what happens after the pilot phase ends? Who ensures that ethical standards are met across all regions? And who is held accountable when AI systems fail or cause harm?

These are not just technical or procedural concerns, they strike at the core of democratic governance in education. When AI tools are used to monitor student performance, allocate resources, or shape how learning is delivered, values such as transparency, inclusivity, and accountability must not be optional; they must be fundamental.

Efforts are underway in the legislature to modernize education and equip the workforce with essential digital skills for an increasingly AI-driven society. Proposals are being considered to embed digital skills and technology training directly into the national curriculum from the foundational levels. The goal is to ensure students are prepared for a future significantly influenced by artificial intelligence.

Concurrently, there is also significant focus on digital transformation. One proposed initiative champions dedicated AI education for government employees. This aims to ensure that policymakers and those implementing new technologies have a solid understanding of AI tools and their implications. Another proposal emphasizes the integration of digital and AI literacy throughout the basic education system. This effort is particularly focused on addressing existing skill gaps and promoting equitable access to digital knowledge.

These legislative proposals collectively highlight a growing recognition that successful integration of AI requires not only technological infrastructure but also strong governance, comprehensive training programs, and a well-defined ethical framework.

Still, amid the questions and growing doubts, there is reason for optimism. Other countries have shown that it is possible to integrate AI in education ethically, equitably, and effectively. The Philippines doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel, it needs the political will to adapt global best practices to local realities. The real challenge is not the technology itself, but how we choose to shape it.

Words by Aljhelyn Piador

Also published in GADGETS MAGAZINE Volume 25 Issue No. 10