When you go back to school, there is something as inevitable as death and taxes: spending time in the library. Libraries hold a lot of physical and digital media. For those who haven’t been to a library in a while, I recall searching for books via a card catalog (this was prevalent even in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when I was still in school), with computer searches available alongside physical card searches. One of the methods libraries use to classify and organize books is the Dewey Decimal Classification, also known as the Dewey Decimal System. Who made this method of searching for books in the library, and why is it so integral to our educational experience?

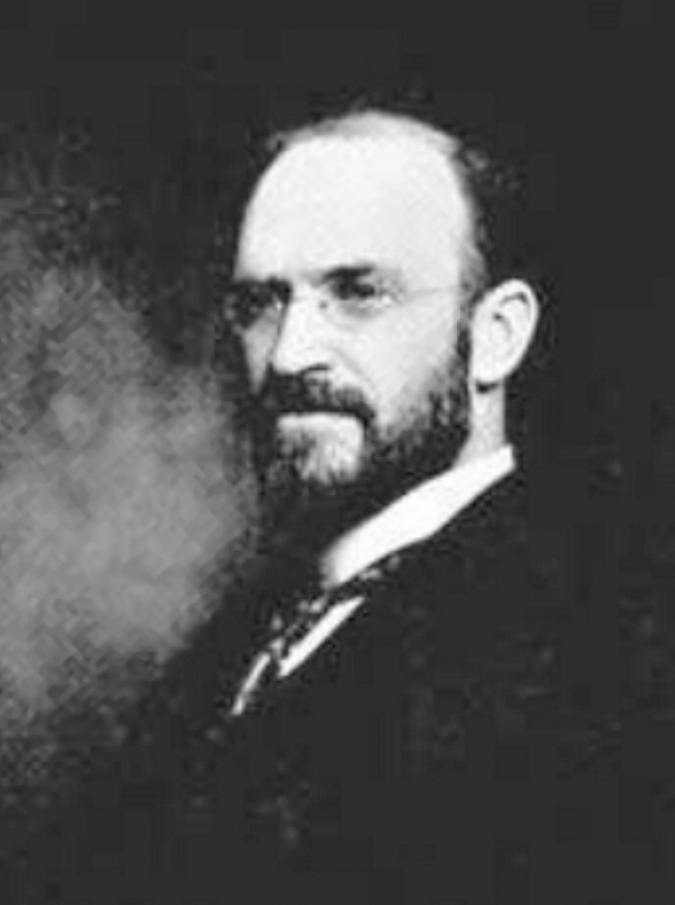

The Dewey Decimal System gets its name from Melvil Dewey, an American librarian who claimed to also be a reformer. He developed his idea of a classification system in 1873 while working at the library of Amherst College. In 1876, he published his ideas in a pamphlet titled A Classification and Subject Index for Cataloguing and Arranging the Books and Pamphlets of a Library. He used this pamphlet to promote his ideas to other librarians and sought feedback for his ideas. However, it is unclear how many people read or commented on his pamphlet, as only one copy with comments survived. The same year, he applied for and received a copyright on the first edition of his index, which totaled 44 pages, 2,000 index entries, and had 200 copies printed.

Numerous other editions were printed, with formal adoption beginning in 1885, when the second edition was published. Dewey claimed that over 100 people offered criticism and suggestions for his format. What made it innovative was that the positioning of books was done in relation to other books on similar topics. Previously, most libraries would arrange the books based on height and acquisition, which, by today’s standards, would make no sense. Dewey even made an abridged version of his system in 1894 to help smaller libraries adapt. Others approached Dewey to translate his classification into French in 1895, and by the time of Dewey’s death in 1931, 12 unabridged versions and four abridged versions had been published.

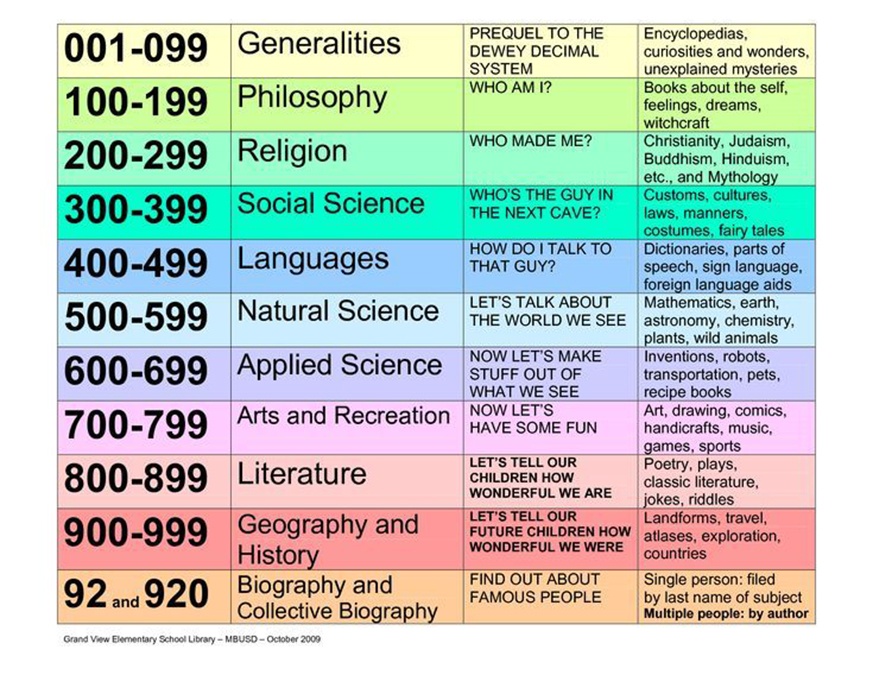

How does the system work? First, it follows a hierarchical classification structure comprising ten classes, which are themselves divided into ten divisions. As for this writing, the ten major classes, notated by call numbers in parentheses, include Computer Science, Information, & General Works (000), Philosophy & Psychology (100), Religion (200), Social Sciences (300), Language (400), Science (500), Technology (600), Arts & Recreation (700), Literature (800), and History & Geography (900), covering nearly all subjects you might learn in school. The following three numbers note the discipline regarding the class. For example, a book about Jesus Christ would be notated under Religion (200), specifically the call number 232. However, to learn about Jesus Christ as a historical figure, the call number would be 232.908. 232 is referred to as the main subject, and the number after the decimal point represents a specific topic. There is a third classification called the Cutter number, which is often based on the author’s last name or title (i.e., the letter in T39 can either indicate the author’s last name or the title of the book). The Cutter number is named after Charles Ammi Cutter, who also developed a classification system alongside Dewey’s system.

While an article on the Dewey Decimal System can run far longer than this space allows, after Dewey’s death in 1931, many libraries found the abridged system to be insufficient, but the full edition to be too cumbersome. The 15th edition, published in 1951, significantly reduced the size of the full edition from 1,900 pages to only 700. An advisory committee was formed for the 16th and 17th editions (1958 and 1965, respectively). By 1993, the first electronic version of the Dewey Decimal System was released; however, hard copy editions are still published to this day. The last major revision to the Dewey Decimal System occurred in 2011.

While the Dewey Decimal System may be daunting to this generation of students, it is vital to know how to navigate the library and become the best student that you can be. While this can be done online today, understanding the origins of this complicated yet effective system can help you better comprehend the library and become a more effective student, potentially leading to an even more effective system in the future.

Words by Jose Alvarez

Also published in GADGETS MAGAZINE Volume 25 Issue No. 10.