If you look back at history, you would find a similar pattern—those not forgotten and those that matter, even up to today, never had it easy. Known to have transfigured her pain and struggles, Frida Kahlo is one amongst few that lives on through her art and her remarkable story.

If the name rings a bell, it’s probably because you’ve either heard about her as a feminist art icon or have recently seen a depiction of her in the 2018 Academy Award-winning Animation, Coco. And although she was portrayed as having a colorful and erratic persona, the story of Frida goes beyond fleeting joys and ideas. Passionate and enduring is what best elaborates her philosophy.

A Truce with Pain

Frida’s artworks have always been known to have depth and meaning embedded in them. As a daring Mexican artist, her works of art have traversed many themes, often exploring, and at the same time denouncing the very norms of singular identity, gender, politics, and social class. Her creations often stemmed from her own realizations of pain and struggle, and how these, given the right time and circumstance, can turn into artifacts that celebrate the diversity and beauty of life.

For someone to emerge victorious in her field given so many disadvantages is a remarkable feat. To be frank, Frida’s many setbacks and hurdles narrowed her chances of success; it was, without a doubt, slim. Unlike many who have traversed the world and sought inspiration through travel while young, Frida lived in a home, famously named “La Casa Azul” almost all her young life. And it wasn’t because she was too lazy to explore or too fearful to take a chance, no. At the age of 6, she was diagnosed with Polio, which caused her to be bed-ridden for 9 months. But as you’ll read later on, Frida is not one that merely allowed circumstance to define her.

After battling her sickness and struggling to recover, Frida fought on. With her father’s support and motivation, she excelled in school and exuded much confidence and bravery, much more than what was expected for a little girl during her time. She explored extra-curricular activities such as wrestling, swimming, and soccer. Coincidentally, it was also at her school where she met her future husband, Diego De Rivera, who happened to be painting a mural at her school. The age gap was huge, 20 years in fact, but the first contact was thankfully only brief, and not to mention, platonic and legal! In one account, however, it was said that Frida jokingly mentioned to a friend that that man she saw would be her future husband.

Another Day, Another Struggle

In 1962, Frida encountered another struggle in her life. On board a bus, Frida was impaled by a steel handrail when the vehicle she was in collided with a street car. The aftermath of the accident was a broken pelvis, as well as several fractures in her spine. For three months she was in a full body cast, but after several weeks, she returned home to recuperate. Despite another unfortunate event, Frida fought on. Parallel to her recovery was her investment in her talent. She was gifted by her parents a series of painting materials as well as an easel which was accessible even in bed. It was during her time of recovery where she finished her first self-portrait which she then later on gifted to Gomez Arias.

An Unconventional Love Story

In 1929, Diego met Frida once again and fell madly in love with her and her talent. Within a year, they’ve tied the knot.Their marriage, however, was far from conventional. Both had several affairs, one of which that Diego had was with Frida’s very own sister! But their love was of a returning kind and one that was strong, albeit strange. Together with her husband, Frida often traveled whenever he was commissioned to work on murals in the US. It was in New York where Frida was often seen sporting her signature bright and bold Mexican Clothing which celebrated Mexican culture.

In 1939, Paris, Frida met Pablo Picasso, amongst other artists. Pablo, along with the curators of the Louvre fell for Frida’s works. This led to the Louvre purchasing one of Frida’s paintings, The Frame, which became the first painting by a 20th-century Mexican artist to be purchased by a museum.

Frida often used art as a medium to express all the physical challenges and struggles she faced. In 1950, she got gangrene in her foot and because of the infection, was then again bedridden for nine months. Eventually, she had to have part of her leg amputated. Despite this, Frida consistently created and stayed politically active. In 1953 she had a solo exhibit and on the opening day, she arrived in an ambulance and even had her bed delivered to the location. But her deteriorating health continued to take a toll on her, and it showed in her artwork, such as her painting the Broken Column. On 1954, she passed, just short of her 47th birthday. But her story lives on. In the 70s’ feminist movement, Frida was crowned as an icon for female strength and creativity.

Behind Three of Frida’s Most Famous Paintings

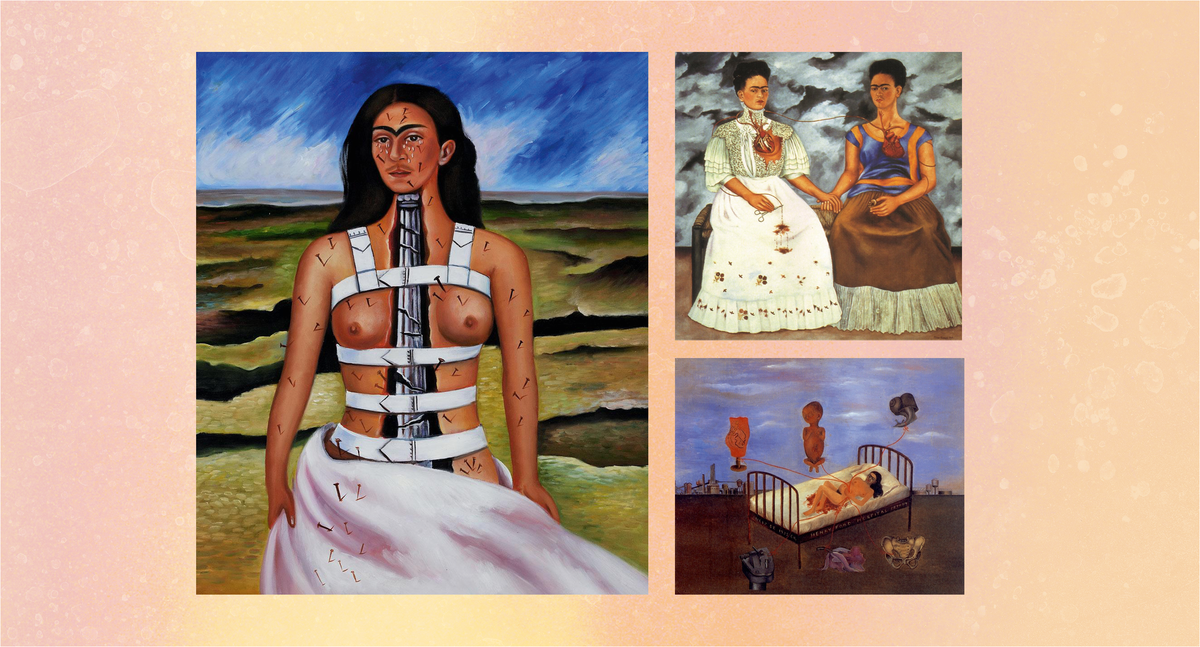

The Broken Column

If there’s anything that was constant in Frida’s life, it’s pain. A series of health concerns and the tragic bus accident of 1962 had left her scarred. Many of her paintings she made were self-portraits which now allow us to take a glimpse of her tortured soul and lifelong struggle. In the painting, The Broken Column, Frida painted herself nude, vulnerable, and wrapped with a steel brace to keep her body upright. Her spine is depicted as a pillar, but that it’s the exact opposite of what a pillar should be—it was broken and unstable. On her body are nails which are violently scattered, and on her face is a melancholic expression like no other.

Henry Ford Hospital

Because of Frida’s problematic health, she had several miscarriages and abortions. In her painting, Henry Ford Hospital, her dark suffering shows. Portraying herself almost like a machine that fuels several entities, we see six different figures which are attached to her by umbilical cords. Among the figures is a dead fetus; a snail which is said to a represent slow suffering; a woman’s open torso; and more. In the painting, all suffering is connected and is rooted in her.

The Two Fridas

Frida and Diego’s marriage didn’t last, as omened by their multiple affairs. Both were polygamous, but they always returned home, until their divorce in 1939. In the painting, we see two versions of Frida— one that was loved, and one that wasn’t. In the painting are a series of distinguishable elements between the two Fridas: one was dressed in a more traditional Mexican clothing, and the other, dressed in European style. Despite being immensely different, both figures are united by their hands, and their exposed hearts are connected, possibly signifying the value of

self-love when there’s nobody and nothing else to hang on to.

Also published in Gadgets Magazine July 2018 issue

Words by Gerry Gaviola

Art by Theresa Eloriaga