The French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague) was the movement-that-wasn’t-exactly-a-movement—at least not in the conventional sense with shared rules, styles and themes—but rather a group of filmmakers with very individualistic and opinionated styles that collectively helped shape the French cinematic landscape.

It arose in the late 50s to early 60s at a time of great change in French society, with a young, vibrant, modern, and mostly middle class population yearning to re-establish their identity through art and literature.

At this time, traditional, mainstream French cinema was stagnating. Although still profitable, the now prominent group of young French intellectuals were getting tired of the high-budget, theatrical post-war film efforts which included a lot of period dramas. The mainstream failed to be so, not being able to catch up with the fast-changing society. The progressive populous now found very little value in these films that were so out of touch with the present.

It was from these intellectuals that the movement was born, spearheaded by critics-turned-filmmakers from the publication Cahiers du cinema which produced the greatest filmmakers of the New Wave—and to purists, the only names—Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette.

These young directors, auteurs rather, concerned themselves with all aspects of filmmaking,taking charge amidst the lack of direction in mainstream cinema without relying on any major studio to finance their films.

Their limitations gave birth to their style—a tight shooting schedule on an even tighter budget, shooting on location instead of on expensive sets, recording audio the same way, not using fancy lighting set-ups, and using new or lesser known actors for their productions.

This caused the auteurs to be creative with their filmmaking, exploring new techniques andaesthetic sensibilities that mirrored their energy and freneticism.

Their cinephilic tendencies, on the other hand, dictated their direction—inspired by the social value of the contemporary depictions in

Italian Neorealism, the poetry of post-World War I French impressionist cinema, and the Golden Age of Hollywood, they played around with the narrative, finding new and inventive ways to tell the story. And since these directors came from the same generation as the moviegoers, the plot and themes in their films were relatable, and quintessentially French.

French New Wave films were perfect examples of how the medium could produce something that was well regarded by both the public and the critics. These works rejuvenated French national cinema and influenced the whole of filmmaking to this day.

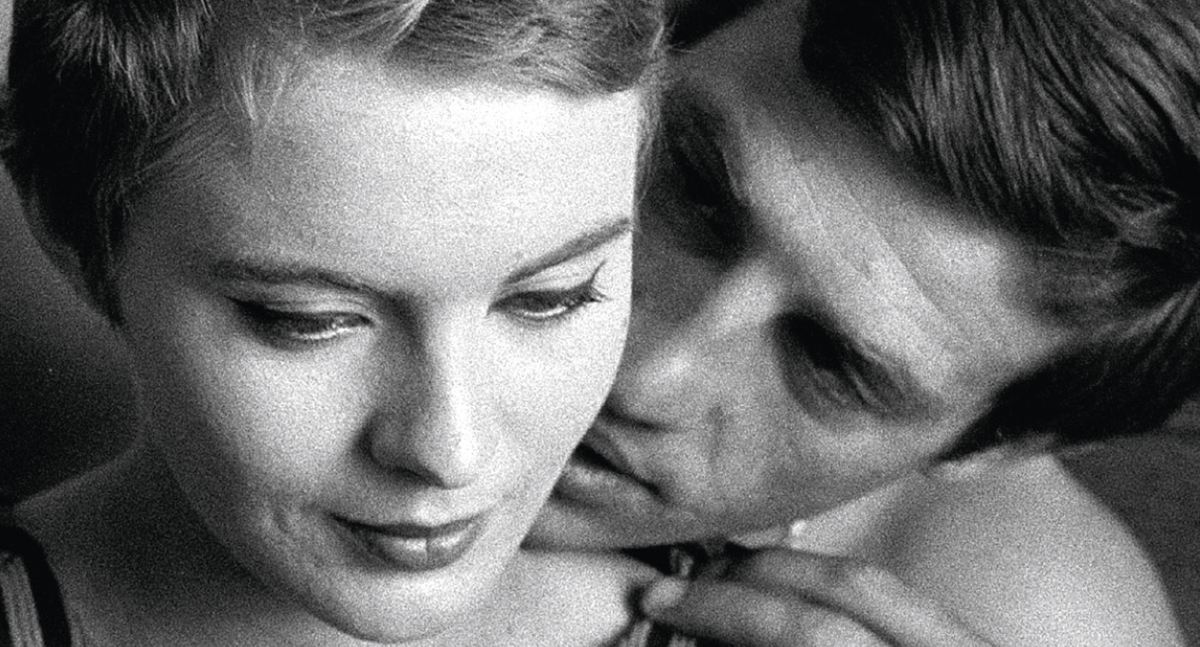

Breathless ( 1960 )dir. Jean-Luc Godard

If there was a film to encapsulate the gritand pace of Nouvelle Vague, it would be the black-and-white film Breathless, Godard’s first full feature effort. This energetic film about two lovers on the run from the authorities went against just about every item on the textbook of mainstream filmmaking at the time, with shaky, and coarse camerawork, and abrupt jump cuts.

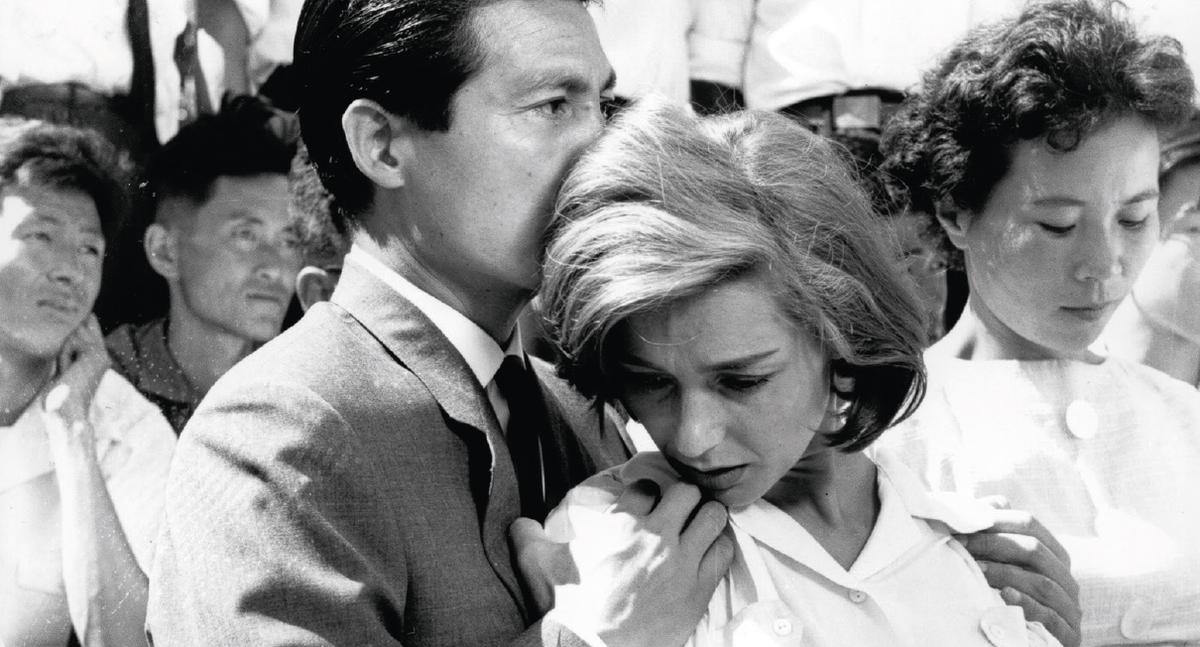

Hiroshima mon amour ( 1959 ) dir. Alain Resnais

So much can be said about how good New Wave auteurs were, that a director’s first feature is already considered a masterpiece. Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour is built around an affair between a French actress shooting a film about peace in Hiroshima and a Japanese architect. Exploring the concept of time, Resnais forms a beautiful narrative wherein past, present and future cut into each other, with themes touching on suffering, loss, grief and forgetting.

So much can be said about how good New Wave auteurs were, that a director’s first feature is already considered a masterpiece. Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour is built around an affair between a French actress shooting a film about peace in Hiroshima and a Japanese architect. Exploring the concept of time, Resnais forms a beautiful narrative wherein past, present and future cut into each other, with themes touching on suffering, loss, grief and forgetting.

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg ( 1964 ) dir. Jacques Demy

Jacques Demy’s love story, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is a parade of color and music, and is one of the most popular films to have come out of the movement. All dialogue is sung in a recitative manner, continuously scored by Michel Legrand. The film also helped launch the career of the beautiful Catherine Deneuve.

Cleo de 5 à 7 ( 1962 ) dir. Agnès Varda

Agnès Varda’s Cleo From 5 to 7 is an introspective, slice of life film that follows the singer Cleo as she awaits the results of her medical test between the hours of 5 pm and 7 pm. Paris serves as the vivid backdrop for Cleo’s contemplation on her existence and her eventual, albeit not necessarily imminent, death.

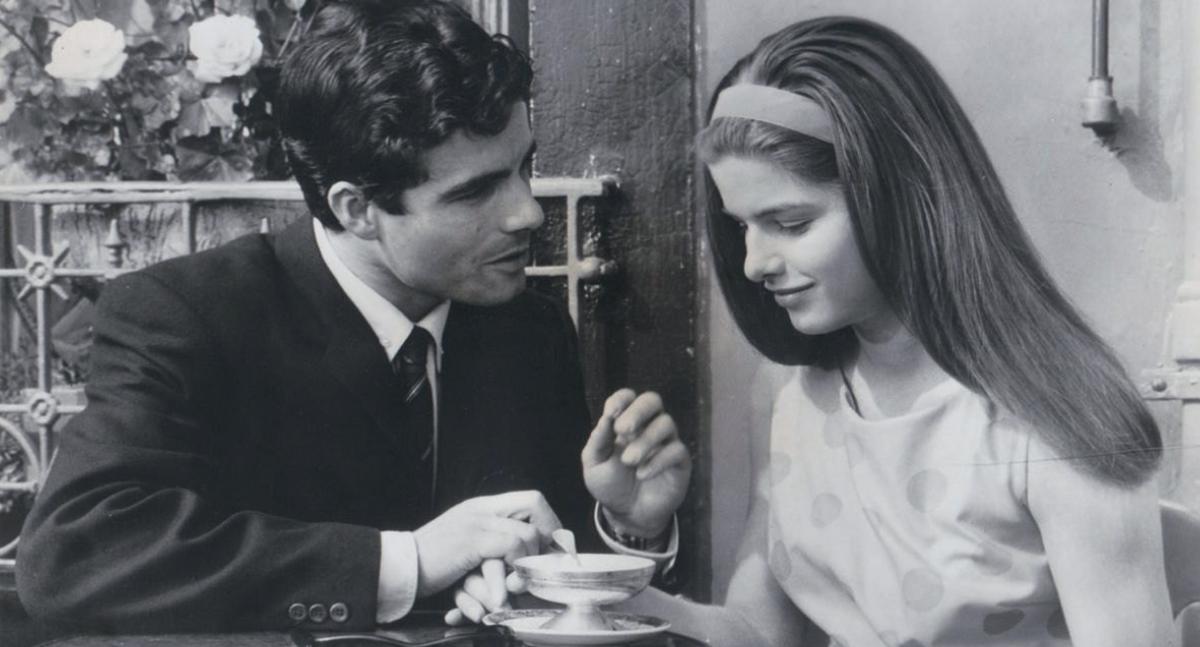

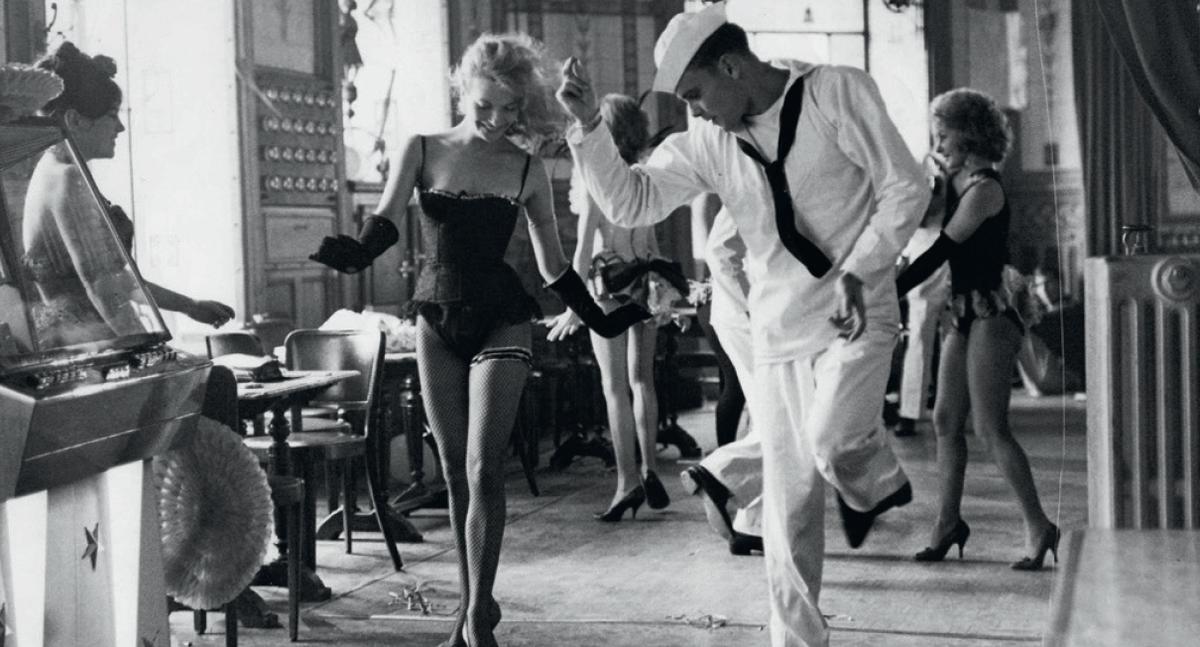

Lola ( 1961 ) dir. Jacques Demy

Demy’s debut, Lola, is literally much closer to home than The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Set in his hometown Nantes, the film focuses on the titular character Lola, a singer in a local cabaret who waits for the return of Michel, her long-lost lover, hinging on a promise he made to her when he left.

Also published in GADGETS MAGAZINE September 2017 Issue

Words by Robby Vaflor