Firearms technology has plateaued over the past few decades. We’ve seen some changes, but they’re such fine, tiny ones that are significant, yes, but not as revolutionary as those we saw in the earlier days of firearms development. This is not to say that improvements in cartridges, or materials used for weapons aren’t great, but the leap from metal to polymer isn’t nearly as profound as moving from the flintlock to even percussion caps. Many incredibly talented minds have tried to solve some of the problems we’ve seen in weapons development, and while we do have the occasional revolutionary optic, or potent new cartridge, we also have more than a few breakthroughs that didn’t quite change the face of firearms as much as anyone had hoped.

Caseless ammunition

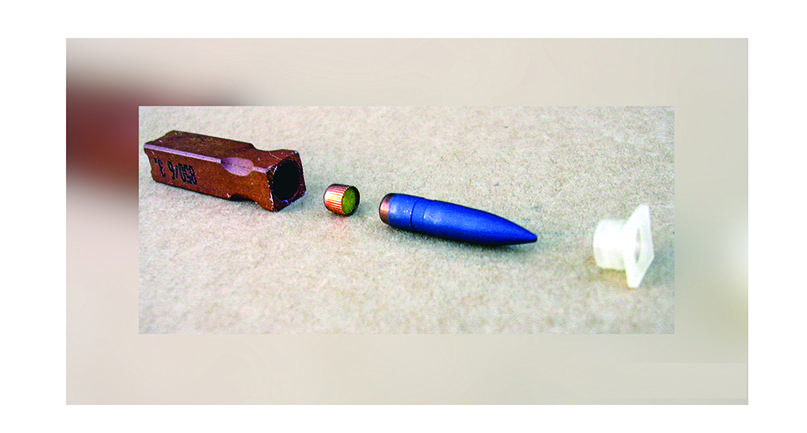

On the very top of the list of developments that failed to take off is caseless ammunition. It will be of little surprise that the main proponent of this technology is Germany. Long on the forefront of firearms design, the Germans hoped to revolutionize small arms with caseless ammo and the HK G11 platform. It’s actually quite amazing, even by today’s standards.

Cased ammo necessitates an extraction step. Once a round is fired, the metal case left in the chamber has to be removed either by hand, or automatically, in order to load a fresh round for firing. It’s plainly obvious that removing this step from the firing cycle will reduce the amount of time a given weapon requires to send more lead downrange. Getting rid of that one step was the main goal of caseless ammo and the G11.

By turning the propellant into a case and expending everything once a round is fired, “case” and all, you can skip the whole extraction process, achieving significant gains in rate of fire with a single barrel and chamber. Interestingly, this was an advantage earlier methods such as paper cases and black powder had over cased ammo, before the benefits of the latter were reaped with self-loading firearms. The caseless ammo worked. HK’s wonderfully retro-looking G11 was living proof. With the ability to fire three-round bursts at a staggering 2100 RPM, the shooter could have the last round of the burst out the muzzle before the recoil impulse was felt, greatly contributing to shooter accuracy and hit probability. It was a great step forward. Sort of. While the rifle had typical German over-engineering problems of its own, the caseless concept was not without fault.

The first and rather important issue 4.7mm caseless ammo faced was fragility. The charge surrounding the projectile wasn’t nearly as robust as a brass or steel case. The inevitable rough handling, impacts, and compression it would see in the field could cause the the propellant cake to chip or break, causing reliability problems with the round. Along these lines, should a round fail to fire for whatever reason, there had to be a way to reliably extract the faulty round from the chamber to keep the firearm functioning. It wasn’t really the simplest thing to get around considering you couldn’t really have any sort of rim on a caseless cartridge.

There was also the matter of cooking off rounds. One of the things brass cases help with is taking heat away from the chamber once it is ejected. With no case to do this, caseless ammunition had to be formulated to be particularly heat-resistant, while keeping the combustibility required to fire. This isn’t as simple as conventional propellants like cordite, and HK had to develop new material with the help of Dynamit Nobel.

Finally, another function of the brass case is to seal the breech on firing a round, giving the bullet a few extra FPS and protecting the bolt. The Germans, in typical German fashion, managed to engineer a way around this as well, but again, this complicated the design and weapon versus traditional cased ammo.

All these issues negated the advantages brought about by the concept, and it died a natural death.

Bullpup weapons

So this isn’t exactly failed firearms technology, but it’s something of a firearms revolution that didn’t quite take off the way people had hoped. Armed forces around the world have, and in fact, still do use bullpup weapons, but their numbers are dropping. France is replacing the FAMAS shortly, and the Steyr AUG is facing the same fate. Sure, the P90 is still going strong, but that might be more a function of the round it was built around than its bullpup design.

The advantages of the bullpup design are well-documented. Having the firing group placed in front of the chamber greatly shortens a weapon’s overall length for any given barrel length against a conventionally laid-out firearm. This gives you better ballistics, greater potential accuracy, and a handier package, essentially giving you a long weapon in a significantly shorter package.

It’s not without its shortcomings. The nature of the bullpup is such that it requires more training to gain proficiency, though it’s not insurmountable with enough time. It’s also typically unfriendly for lefties, as the cases usually eject right alongside the shooter’s face—though some bullpup weapons, such as the FS2000 and FN P90 get around that by moving things around a bit. There’s also the matter of being rear-heavy, as that’s where most of the weapon’s mass is located, so overall balance is affected. They also tend to have terrible triggers that rely on transfer bars, making them just a little more difficult to shoot. It was a novel idea and a usable solution, but it seems as though militaries are ready for something else.

There are a few more technologies that we’ve yet to cover, so stay tuned for the next installment!

Also published in GADGETS MAGAZINE September 2016 issue.

Words by Ren Alcantara