Is innovation good or bad? The intent of innovation is to improve on a previous idea and make it more efficient or even better than that idea. However, it depends on who you ask. Sometimes innovation can spark success. Sometimes it can utterly fail. It can also teach valuable lessons on what to do next time. Failure is often the motivation to try again — if, at first, you don’t succeed, right? In terms of video game consoles in the 1990s, there were plenty of commercial and critical failures. The Virtual Boy happened to be one of the few blemishes on Nintendo’s otherwise excellent track record.

The story of the Virtual Boy goes back to 1985. Nintendo was not yet a household name in North America. A company called Reflection Technology Inc. (RTI) produced a stereoscopic head-tracking prototype called the Private Eye. The company demonstrated the technology to major toy companies such as Mattel and Hasbro. Ironically, Sega turned this down because of its single-color display and the potential for motion sickness. While Sega took astronomical leaps into the unknown when it came to innovation, Nintendo also had its reputation for doing so. However, the products centered more around the user experience rather than trying to be too far ahead of their time.

Nintendo was enthusiastic about this new technology. The late Gunpei Yokoi, who invented the Game & Watch and Game Boy, saw this as something competitors would find difficult to emulate. He nicknamed the project “VR32” and saw it as a way to encourage more creativity in games. They then signed an exclusive agreement with RTI to license the technology for the display. In the early 1990s, Research & Development 3 was working on the Nintendo 64, so the other two R&D units could free up their time to develop the Virtual Boy. Development began in 1990, and Nintendo even built a dedicated manufacturing plant in China for the Virtual Boy.

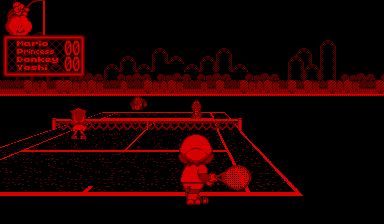

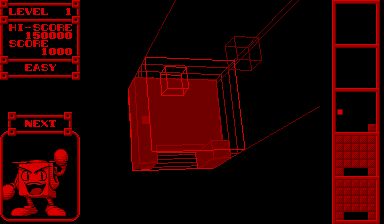

The Virtual Boy was most well known for its red and black graphics. Having actually played the Virtual Boy, I have never really understood their choice of red and black. Still, after researching this article, the reasoning was simple: red LEDs were the cheapest, and not having a backlit screen made the user experience more immersive. Nintendo had to also remove the head tracking feature for both health and legal reasons, giving it the design of goggles on a stand — not the best design choice for what was supposed to be a futuristic console. But this was the 1990s, and trying to develop something we would take for granted today was a pretty Herculean task.

The Virtual Boy made appearances at major video game and electronic conventions such as E3 and the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). Nintendo projected sales of 3 million hardware units and as many as 14 million games sold by March 1996. Was this arrogance, or was virtual reality finally here to stay? One telling sign that this would be a commercial failure was the lack of involvement from Shigeru Miyamoto, according to author David Sheff in the 1999 edition of his book Game Over. Yokoi’s reluctance to release the Virtual Boy in its current form was another factor, yet Nintendo pushed it to market in 1995 so that even more resources would be freed up for the Nintendo 64.

Nintendo released the Virtual Boy in the summer of 1995 at USD179.95 (about USD330 in 2021). It toed the line of not being as powerful as a console, but more powerful than the Game Boy. Some critics had called it a more evolved version of the View-Master. Nintendo reported sales figures of only 770,000 and claimed to have spent USD$25 million on marketing. However, there were reports of dizziness, nausea, and headaches when using the Virtual Boy, with some contemporary articles suggesting that prolonged use could even cause permanent brain damage.

Nintendo also heavily focused on the technology of the Virtual Boy rather than the games. Only 19 games were released in Japan and 14 in North America. The console performed so poorly that the plug was pulled on this particular project in 1996, less than a year after its release. This may have been good for Nintendo, as the company released the Nintendo 64 later that year, which sold nearly 33 million units. This might have blunted the negative PR from the Virtual Boy.

Sheff placed the failure of the Virtual Boy squarely on Gunpei Yokoi, who left the company shortly after Nintendo discontinued the Virtual Boy. As a result, RTI went out of business by 1997. Yokoi, unfortunately, passed away in a car accident in October 1997. Yet there was some hope for Nintendo to return to VR, even though the prospects were bleak. In 2010, then-Nintendo of America President Reggie Fils-Aime even said he was unfamiliar with the Virtual Boy when asked if any of the Virtual Boy games would come to the Nintendo 3DS’s Virtual Console.

Some hobbyists had taken to bringing emulated Virtual Boy games to the Samsung Gear VR in 2016 and the Oculus Rift in 2018. Former president of Nintendo Tatsumi Kimishima also said in 2016 and 2017 that there might be the possibility of a VR peripheral for the Nintendo Switch. Still, as of 2022, this has not yet become a reality. The Virtual Boy only lives on as an example of a commercial failure and innovation that we can all learn from.

Words by Jose Alvarez

Also published in Gadgets Magazine January 2023 Issue